As 2010 drew to a close, the international news remained focused on the fallout from the year’s big events: the start of the Arab Spring, the Haitian earthquake, the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. Movie-goers were excited by recent smash hits the The King’s Speech and The Social Network, and music charts were dominated by young whippersnappers like Usher, Nelly and Eminem. In politics, meanwhile, David Cameron was just starting out on a happy coalition with Nick Clegg in the UK, Nicholas Sarkozy still had bold plans to transform France, and a youthful Barack Obama was in the appetizer days of his presidency. And in the Netherlands, Mark Rutte, a former mid-level manager at a peanut butter company, had recently become Prime Minister.

More than a decade later, a great deal has changed. Political careers have crumbled, revolutions have faltered, and the global economy has recovered from one once-in-a-generation crisis just in time to have another. Sarkozy has been convicted of corruption, Cameron is mooching in a shepherd’s caravan, and Obama vies with Prince Harry for the most lucrative deal with Netflix. Mark Rutte, however, is not only still in power, but likely to stay there. Polls suggest that when the Netherlands goes to the polls on 15th-17thMarch, Rutte’s VVD party will win not just the most seats in parliament, but more than twice as many seats as any other party. An upset is always possible, but it looks likely that after more than a decade in power, and following a recent economic crisis, deadly pandemic, riots and much else, the new boss will end up looking exactly the same as the old boss. As I once wrote elsewhere: Rutte is the Japanese knotweed of Dutch politics: impossible to get rid of.

Rutte’s ongoing success is in some ways a mystery. Whatever one thinks of his politics, he’s no great visionary. In speeches and press conferences he’s a good communicator, but there’s no soaring rhetoric: the general tone is less ‘Yes We Can’ and more ‘I Suppose We Might’. Despite his long tenure, Rutte’s record in office has also been, at best, blandly competent rather than glory-filled or transformative. Some things have arguably got better on his watch and other things worse; in a decade of wandering around the Netherlands talking to people, I’ve met plenty who respect him but almost no-one who was really a passionate fan. And perhaps most importantly, the government’s performance during recent crises has been patchy at best. Deaths during the coronavirus pandemic have been lower in the Netherlands than in some comparable countries but higher than in some others, lockdown policy has often seemed confused, and the national vaccination programme has moved about as fast as an ice skater stuck in a grassy cow field. In January, Rutte and his cabinet even suffered the indignity of having to resign en masse; brought down by a scandal involving gross mismanagement of the benefits system. For a man whose political sales pitch hasalways essentially been: “I’m nothing special but I’ll avoid drama and you’ll hardly notice I’m here”, the sense of rolling crisis has been damaging.

In other ways, though, it’s not hard to see why Rutte remains popular. Firstly, there’s the simple fact that for many Dutch people, life during the pandemic has not actually been that bad at all. Yes, deaths have been high, livelihoods have been lost and many people have suffered badly. But the Dutch have also enjoyed a degree of freedom which would be unheard of elsewhere. Last summer, Parisians faced fines if they left their homes without proper paperwork and children in Spain were barred from leaving their homes, but in most Dutch towns life remained quite normal, with non-essential shops open and few restrictions on personal activity. Even now, under a “strict” lockdown, people are still allowed visitors at home and are free to travel around the country; schools are open and you can visit non-essential shops if you make an appointment. When I visited Delft briefly last week, the streets were packed, with long lines at the ice cream shop, groups of people meeting up for coffee and perhaps one in a hundred pedestrians wearing a mask in the street. Bars and restaurants were closed, but otherwise an alien who landed from Mars would never guess anything had changed since 2019. If one accepts James Carville’s maxim that the only thing which matters is the economy (stupid), then it’s also not hard to see why Rutte has remained popular. The Netherlands’ economy has, like everyone else’s, taken a battering over the last year, but European Commission statistics show that in January unemployment was one of the lowest in Europe, with Dutch people less than half as likely to be out of work as French people. Many businesses are struggling now, but most voters are (in purely economic terms) better off than they were in 2010, and there’s a sense that after ten years with Rutte in charge, we could do a lot worse than another ten years of the same. The election campaign itself has felt strangely muted, with live events cancelled and most campaigning happening online. Trivial issues like chat show roastings have been discussed in soul-destroying detail, while some critically important ones are mentioned only in passing. For an observer this makes the whole process oddly boring and bloodless – but also benefits a politician who aims to preserve the current order rather than upend it.

More broadly, Rutte’s popularity also reflects the prevailing Dutch preference for a certain type of leader. Despite all the free-loving weed-smoking international stereotypes, this is at heart quite a conservative country, in both senses of the word: there have been only five Prime Ministers in the last forty-four years (all middle-aged white men); and by my rough count, right-leaning parties together look set to win about two thirds of the vote this time. For many Dutch, the only thing worse than a crisis is change, and Rutte feels like the living embodiment of the status quo: a warrior monk -type figure with no obvious hinterland. He’s unmarried and famously lives alone in a modest apartment, driving a second-hand car, teaching part-time, cleaning up his own spilled coffee and riding a bike between important meetings, half-eaten apple always in hand. When his mother died last year, Rutte didn’t visit her as to do so would have breached lockdown rules; something it’s hard to imagine some other statesmen doing. Inan age of massive motorcades and enormous security details, such ordinary behaviour is enough to make a leader go viral – but also perfectly pitched for a country where humility is prized, and a serious insult is “doe gewoon normaal” (just be normal). When I bumped into Rutte a couple of years ago at a scruffy little Rotterdam café, he arrived alone on foot, without any security, waited for a table and then ate some apple pie with a friend, who mostly seemed to ignore Rutte while fiddling with his phone. When my dog tried to steal a bite of his pie, the Prime Minister didn’t seem to mind.

All this isn’t to say that Rutte is uncontroversial. Many people are alarmed by the turn the Netherlands has taken in the last decade; feeling that (as in the UK) years of austerity have steadily eroded the quality of public services. While the quality of Dutch public services remains remarkably good overall, there are growing problems in some areas. Homelessness is rising and housing in some big cities is becoming ruinously expensive. The recent benefits scandal (Toeslagenaffaire) was a truly ugly business, involving racial profiling of benefits claimants, false accusations of fraud, families forced into bankruptcy and years of obfuscation and buck-passing by those in power, including the Prime Minister. More generally, Rutte has also had a bad habit of telling right-leaning voters whatever they want to hear, in the hope that they won’t desert him in favour of more extreme parties. This modern, liberal, media-friendly leader has openly told peoplewho didn’t abide by traditional “Dutch values” to go back where they came from, banned Muslim headscarves on public transport and cheerfully agreed with a member of the public who shouted out that he shouldn’t give any money to Italians or Spaniards. The mythical current immigration ‘crisis’ often seems to get priority over the real coronavirus one. Just this week, Rutte was telling reporters that if refugee numbers surged in Europe again, his response would be “grenzen dicht” (borders closed) – something which he consistently argued was impossible when the pandemic was spreading. Such comments have horrified the liberal Twittersphere, and there’s a strong case to be made that by “talking tough” on issues like Europe, Islam and immigration, Rutte has helped fan the flames of intolerance, emboldening the same far-right parties which he hopes to defeat. However, there’s also little doubt that such behaviour is popular with a huge number of Dutch voters. The Prime Minister’s ability to dodge a scandal remains impressive. Teflon Mark could fall into a dairy cesspit and still come out looking clean.

To international observers, perhaps the most notable thing about Rutte is the aforementioned lack of vision. In Anglo-Saxon world in particular, we’ve become somewhat accustomed to the idea that our leaders should be bombastic or at least impassioned, giving stirring speeches and pledging to deliver a brighter tomorrow. Dutch politics, however, doesn’t really work like that. While a British or American or French leader’s job is partly managerial and partly symbolic, in this country there’s little sense of the Prime Minister being a source of inspiration or moral authority. In a system with dozens of different parties in parliament, and three or four governing together in coalition, the job of Prime Minister is more like that of a marriage counsellor: coaxing unhappy partners to stick together a little longer rather than trying something new. The emphasis is not on grand visions or radical change, but on the dull business of keeping everyone not-too-unhappy. In that context, it’s perhaps unsurprising that a former HR manager like Rutte would do well; not just tolerating the dull grind of inter-party management but seeming to thrive on it. After joining the VVD as a teenager, Rutte rose steadily through the party ranks and has proved a consummate pragmatist, apparently happy to adopt or ditch principles depending on what’s in fashion. Early in his tenure he partnered with the far-right firebrand Geert Wilders; now with leftish-liberals D66. Until the pandemic, this shape-switching was arguably quite successful, and helped the Netherlands remain on an even keel through crises including the MH17 disaster, the aftermath of the financial crisis, Brexit and Trump. While there’s certainly much to criticise about Rutte’s tenure, it’s still hard to find anyone who speaks ill of him personally, rather than of his policies, and there’s never been a hint of personal scandal. On the international stage, the natural comparison is with Angela Merkel: another centrist-conservative north European leader who’s been around longer thanTwitter. To me, however, Rutte also seems like a kind of Dutch Joe Biden: a cheerful dealmaker whose greatest strength is his ability to appear like a decent guy while herding cats in the same direction – yet who has no transformative agenda beyond keeping us in 2012 forever. Rutte is the kind of guy you’d be happy for your sister to marry, but also forget ten minutes after meeting at a conference.

During the current election campaign, Rutte has alsobenefited from the woes of his rivals. On the left, D66 (the Dutch version of the Liberal Democrats) have had a good few weeks, campaigning feistily on liberal issues and effectively distancing themselves from their own record in power. They may well deliver a modest surprise next week, awarding Sigrid Kaag the role of kingmaker. Others (GroenLinks, PvdD) have struggled to gain attention at a time when most people are focused on issues which lie somewhat outside those parties’ comfort zones. GroenLinks leader Jesse Klaver seems manifestly decent but is no longer the new kid on the block, didn’t break through in televised debate, and his talk of climate crisis feels less urgent when people are worrying how to teach their kids while also chairing that 9am Zoom meeting. The centre-left PvdA (Labour Party), meanwhile, has run a solid campaign but was battered by the benefits scandal and still hasn’t recovered from the trauma of served in coalition with Rutte during his last term, dismaying many of their leftist supporters. On the right, Rutte’s current coalition allies the CDA have gained a bit of zip under new leader Wopke Hoekstra, and will likely do quite well. But Hoekstra has also made some mis-steps campaigning, and (like Rutte) has often clumsily pandered to the far right on immigration and Europe. Like other coalition partners, the CDA struggles a bit to claim credit for the government’s recent successes while distancing themselves from recent crises, and to appeal to new voters while satisfying their conservative base. Compared to Rutte, Hoekstra looks cooler, younger and a good deal more dashing – but also not quite fully formed; someone who (like Jens Spahn or Keir Starmer) could be leading the country in five or ten years’ time but could also fall short of expectations. A Hoekstra premiership remains plausible, but his rising star could also turn into a shooting one.

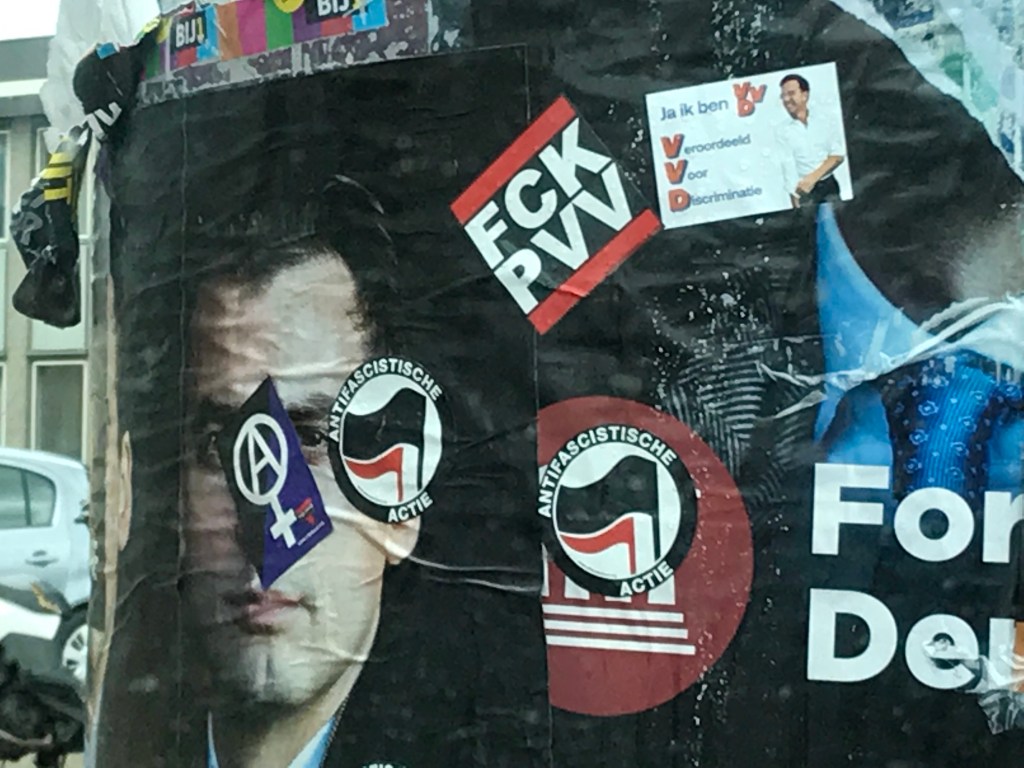

In parts of press, the focus is inevitably on the populist right, and the two men who lead and exemplify the two most notable rightwing parties: Geert Wilders and Thierry Baudet. During this election cycle, Wilders has received less frenzied media attention than in the past – after decades in national politics, he’s no longer news, and his angry-at-everything schtick has worn a bit thin. Most polls show support for Wilders’ PVV party falling a bit, and the party has lost seats in both the Dutch Senate and the European Parliament recently. The party has also provided a rather un-Dutch salacious scandal recently, with one of Wilders’ key parliamentary supporters accused of forcing his ex-wife to have sex with police bodyguards inside the Dutch parliament. Wilders has himself admitted that the current climate favours the incumbent rather than challengers like himself, saying “corona is the number one issue” and “in a time of crisis, people tend to rally around the flag”. But there’s also no doubt that when polling day comes, he’s still a force to be reckoned with. It’s surprising how much media coverage and punditry neglects to mention the fact that the PVV consistently comes second in the polls, behind only Rutte’s VVD, and has roughly doubled its vote share in the last year and a half. More entertainingly, there’s also Thierry Baudet, a sort of Millennial-friendly reboot of Wilders who crashed onto the political scene a couple of years ago, won huge attention with his ageing-Gap-model looks and slick, YouTube-friendly style of campaigning. Baudet often seems to get more attention than he deserves, but there’s again little doubt that he is (or at least was) an influential figure; niftily stealing votes from Wilders and winning shock first place at the provincial elections just two years ago. Since then, however, Baudet’s fortunes have been undermined by party infighting and scandals about alleged anti-Semitism. In the summer of 2019, the FvD was polling at about fifteen percent, but it’s now it’s barely a fifth of that level. During the campaign, Baudet has also taken an alarming swerve further to the right, holding lockdown-busting rallies, claiming the Nuremberg tribunals were illegitimate, alleging vast international conspiracies and opposing coronavirus vaccinations. This may all represent an unveiling of what Baudet really thinks, but it feels to me more like a strategic choice: desperate to retain his influence, Baudet looked around spotted a gap in the market for a party which is basically an angry pro-Trump Facebook page brought to life. It’s easy to mock, but his analysis doesn’t seem wrong: amazingly, the FvD’s projected vote share has risen sharply since Baudet went full moron. Overall, though, it’s clear that both Baudet and Wilders have painted themselves into a corner. Their parties are certain to win a decent number of votes, but also almost certain to be locked out of government, given the unwillingness of other major parties to enter coalition with them.

After the upsets of Brexit and Trump, it would be foolish to put too much faith in pre-election polls. But at this point, Rutte’s lead is so big that it’s almost guaranteed he’ll fall a little short of his previous peak yet still crush all rivals. Coalition negotiations will take at least three months, and could well deliver atweak to the shape of government, with a smaller party like the CU perhaps dropping out and another stepping in as a substitute. There’s also still anoutside chance that smaller parties could do well enough that they can make their participation in government conditional on a change at the top, and force Rutte out. (In the Hague, people talk of the possibility that Rutte could serve another couple of years, then step aside without completing a full term, perhaps to take a top job in Brussels). It’s also possible that the pandemic could affect the result in unexpected ways – for example, encouraging older voters to stay home, and hence boosting prospects ofparties which draw support from the sections of society who use TikTok rather than Yahoo Mail. Newer, smaller parties like alt-right JA21 and “D21” pro-Europeans Volt will likely grab a few seats. Judging by his recent tweets and speeches, there’s also a real possibility Baudet will reject any election result he doesn’t like – an eventuality which I’m not sure Dutch society is well prepared for. Yet after the most turbulent and traumatic year in postwar history, the most likely election outcome remains the most boring one: more of the same. Overall, Dutch voters look like customers in a local takeaway restaurant: spending ages browsing a long menu of choices, before ending up ordering that favourite old dish they choose every time anyway. It’s another odd irony: an election contested by dozens of parties may deliver an utterly bland outcome; and the soon-to-be longest-serving Prime Minister in Dutch history could be someone who leaves almost no visible legacy. What would another decade of Rutte meanfor the country? No one seems to know, including the man himself. But we may be about to find out.

Wonderful essay and you could have not described the situation more than accurately! Compliment! Dutch politics after 37 years of living here is fundamentally boring and I have decided for the first time not to bother to vote! In my opinion a waste of time! Too complicated and no imagination for upcoming future generations!, For god sake 35 parties to choose from and what I vote for which is business will never get a chance!, Forget it!,,

LikeLike

Typical heavily biased report devoid of objective balance. Labelling the most active opposition party as “full moron” is emotional and devoid of supporting evidence. That most of the Dutch political parties support the agenda of the via Bill Gates (an IT entrepreneur previously convicted of anti-trust) controlled GAVI controlled WHO controlled public health ministers around the world, will not automatically say that this majority is correct. At one time it was popular in Germany to execute Jews, Roma and the disabled. At the current time in The Netherlands it is popular to remove children from their home for no reason: https://notesfrompoland.com/2020/09/21/polish-court-rejects-extradition-of-asylum-seeking-family-to-barbaric-netherlands/ 10 more years of disproportionate lockdowns, experimental mRNA drugs and stealing 53,000 innocent children from their overwhelmingly innocent parents? I surely hope not.

LikeLike

Thanks Conrad! I take it all back, your message shows that Baudet’s supporters are entirely rational.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Ben, like it or not that is the current hierarchy within the global public health order. Bill Gates does pull the strings of the WHO via GAVI: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/GAVI . And from there it is broadly apparent the WHO pulls the strings of the definition of and the response to the Covid-19 virus.

Also like it or not the number of removed children in The Netherlands the past five years has more than doubled from 25,000 to 53,000, one of the highest per capita rates in the world. Without any expert being able to point to a drugs, alcohol or other crisis to justify it.

Also like it or not The Netherlands has just re-elected a prime minister in Rutte who recently resigned due to an admitted wide-scale rule of law failure (toeslagenaffaire) which covered most his 10 year reign. is that supposed to be a rational response? In most Western democracies such politicians automatically resign and the population is in any case not irrational enough to re-elect them.

LikeLike

Very nice essay! Reading it after the election has proved to be interesting- some predictions didn’t necessarily ring quite as true as was expected. However, I am a little concerned about the growth of the far-right. Last election, ~16% of votes cast were for far-right parties, whereas Baudet and his fashy haircut gang seem to have capitalised on the fears of some of the youth and received, with the PVV and FDP, over a fifth of the vote. I’d be really interested to see whether you think that this is a peak in far-right support, or more of a foretelling before controlling an even more significant portion of the Tweede Kamer.

It would be refreshing to see if there’s anything we can actually do to prevent this worst-case outcome before the 2025 (I assume?) elections- although by then I may have left the Netherlands for greener pastures.

Either way, you’ve earned yourself a new follower!

LikeLike

QAnon is strong with this one. Hardly worthy of a polite response. Moron is a very accurate way of describing a racist, xenophobic, science-denying proto-fascist politician. Conrad’s posts are full of so many conspiracies that I almost lost count.

LikeLike

Dear Jeffh, every argument in my post is fact based either supported in the post or easy to verify on internet. Throwing around childish baseless ad hominem attacks proves nothing other than the shallowness of your current thought patterns. You can surely do better,

LikeLike

No, I am afraid it is you, Conrad, who is making childish assumptions. As the character Sefton (William Holden) said in the film classic “Stalag 17”, ‘you have added two and two and come up with four only the answer isn’t four’. I am no fan of Bill Gates, but simply linking him with efforts to globally vaccinate vast numbers of people from SARS-Covid 19 does not prove anything other than he is using a tiny portion of his vast wealth for philathropy. I know exactly what you are trying to suggest: that there is a vast conspiracy involving Gates, George Soros and other wealthy liberal philanthropists who are in league with pharmaceutical companies to promote their influence by pushing vaccines to deal with a virus that you think is either exaggerated in terms of its effects on human health or was secretly bioengineered in a lab somewhere and released upon the world in order to control populations and suppress their freedoms. Or some such utter nonsense. Straight out of the X-Files of QAnon. Let me guess: you are also deep into the latest conspiracy of ‘the great reset’ whereby a cabal of powerful, liberal/left organizations and individuals are secretly using the pandemic as cover for a nefarious, wicked plan to seize control of global governance to suppress individual freedoms. I suspect that you are also a climate change denier as well.

People like you do not fool me, Conrad. Ben quite rightfully called out politicians like Baudet and Wilders, labeling them for what they are. I would not necessarily say that they are complete morons, however, because in pushing their borderline proto-fascist garbage they are dangerous. They promulgate anti-scientific drivel for sure, and that is what is most problematic. Despite Baudet’s puerile assertions, SARS-Covid 19 is a grave threat to society and measures are necessary to suppress or contain it. If we immediately go back to BAU, as many on the far right want, then the consequences for society will be dire. Thankfully, thus far, common sense prevails.

LikeLike